Sacred Land, Scarred Land

Over 60 abandoned uranium mines exist on Navajo land in the Monument Valley area at the state border between northeastern Arizona and Utah. Mines were operating between 1944 and 1962. The Navajo people have experienced injustice and betrayal since the first miners arrived on their lands. Malpractice of depositing radioactive mine tailings near settlements caused increased cancer rates and continuously contaminated natural resources, such as air, soil and groundwater on which the Navajo depend.

Road sign outside of Cameron, Arizona. Forty years after the last uranium mine was closed, the Navajo Nation continues to grapple with environmental issues, cancer cases, birth defects and sickness related to contaminated groundwater, soil and polluted air.

-

This section is providing a historical overview, with archival material and photographs, from the pre-mining era to mining activities in the Monument Valley area from 1944 to 1962. Read more…

-

In this section we will look at the current situation, where and how millions of tons of radioactive waste is stored in disposal cells across the Navajo land. We also look at the geology of the valley and design of the landfills. Read more…

-

For decades uncovered hills of mine tailings and waste from processing sites and mills penetrated the ground with radioactive material which eventually contaminated groundwater in aquifers. This contamination is irreversible forcing residents to buy bottled water. Read more…

-

Many places in or near Monument Valley are sacred to the Navajo people. It is where they perform traditional, spiritual ceremonies, rituals and chants. Read more…

-

With artistic methods, such as smoke or light painting I try to make visible what our eye can’t see. Radiation is an invisible threat to the local residents. Read more…

All photographs (c) 2022 by Stefan Frutiger, unless otherwise posted.

The uranium-vanadium mineral carnotite was first noted in the valley by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) geologist Herbert E. Gregory in 1917. In 1921, an occurrence of uranium-vanadium minerals was discovered north of Kayenta by John Wetherill, a Kayenta trader. This occurrence was investigated by Frank Hess, USGS and by several prospectors.

Historical Context

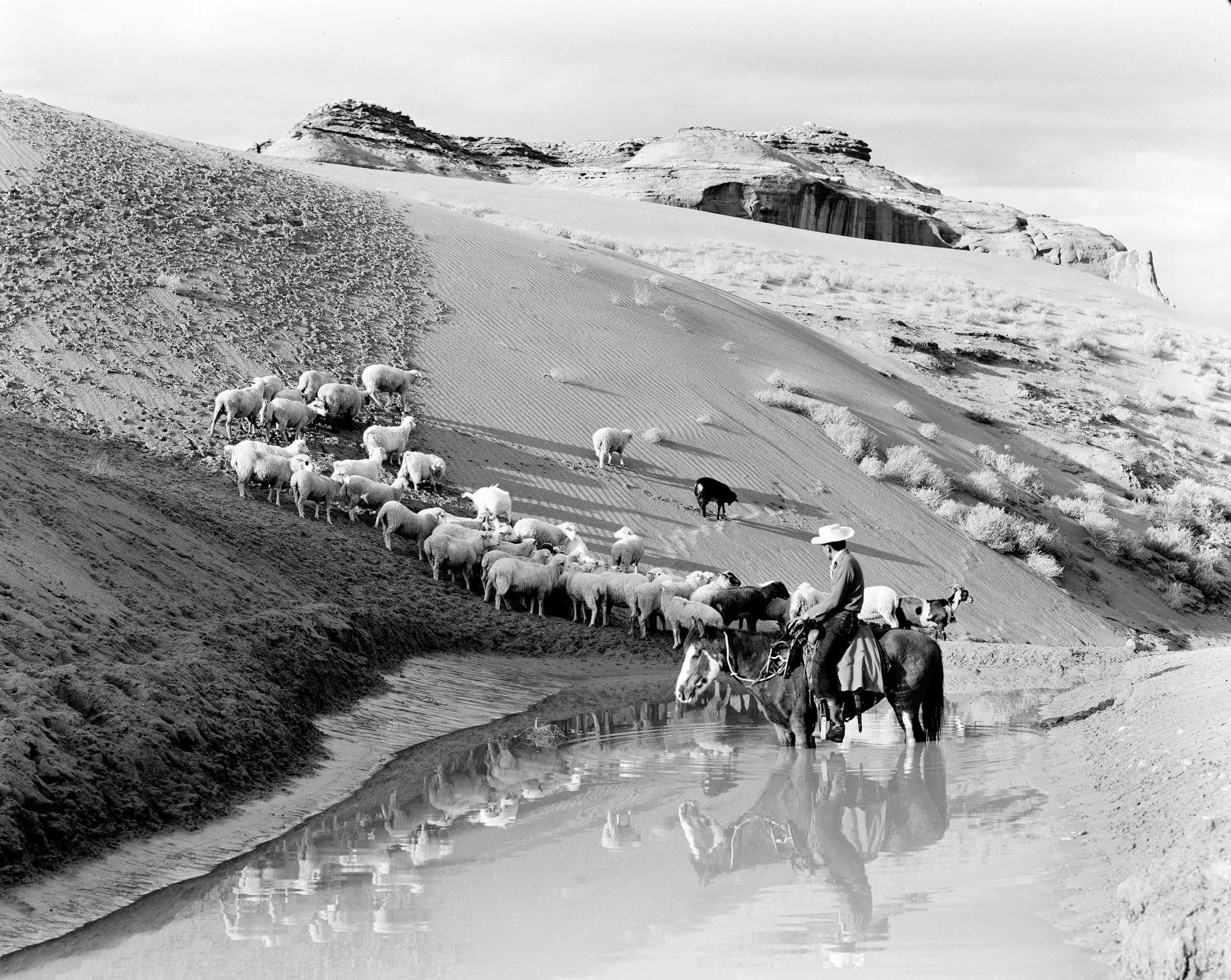

Navajo Indians in Momument Valley. Monument Valley- Sheep at Sandspring + Indian. By Josef Muench. 1950-1970.

Cornfield in Monument Valley, Arizona. by Philip Johnston. 1920s

On October 1, 1942, the Office of Indian Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior, offered for sale a lease on 20.06 acres north of Kayenta. This was probably the site of the Wetherill discovery. When the bids were opened on October 22, 1942, Vanadium Corporation of America (VCA) was the highest bidder with a bonus bid of $739.83. This lease was named the Monument No.1 by VCA. Mining began in December 1942 and continued through February 1944. Shipments resumed in October 1945 and ceased in January 1946. This vanadium ore was shipped to a mill at Monticello, Utah. Total production was 3,525 tons of ore that averaged 1.94% V205.

Monument Valley - View of Lookout, Mittens, Sisters and Window area. By Josef Muench. 1950-1970.

Navajo Indians in Monument Valley. Monument Valley. North Window- tree on right. Joyce Betty. By Josef Muench. 1950-1970.

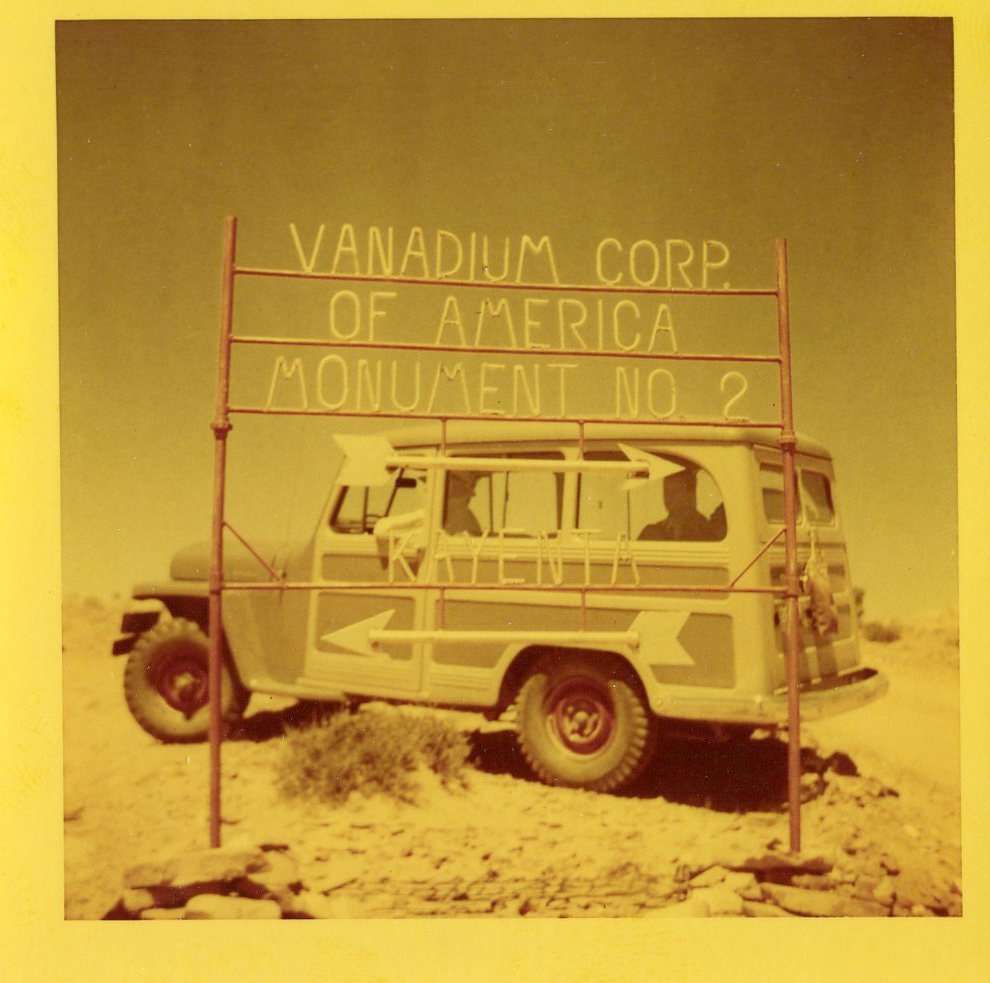

In 1942, Luke Yazzie discovered carnotite mineralization in the Cane Valley area in eastern Monument Valley. He told Harry Goulding, a local trader, of this discovery, who contacted VCA. As news of this discovery spread the area was investigated by several firms and individuals. Due to the interest in the area, the Office of Indian Affairs offered for lease 1,845 acres in the Cane Valley area on July 31, 1943. When the bids were opened on September 3, 1943, VCA was the only bidder with a bonus bid of $3,000. The lease was reduced to two plots totaling 42.09 acres in March 1944. VCA named this lease Monument No. 2. Shipments to the Monticello, Utah mill began in October 1943 and continued until April 1944. Later shipments were made in February and December 1945 and January 1946. Total production was 487 tons of ore that averaged 1.40% V205. At the Monticello mill, the Manhattan Engineer District (MED) secretly recovered uranium from the carnotite ores.

Navajo Indians in Monument Valley. Navaho Boy on Pinto Horse & Colt. By Josef Muench. 1950-1970.

Navajo Indians in Monument Valley. Monument Valley. Inside Trading Post. Harry trading with Sally Laughter + Daughter. By Josef Muench. 1950-1970.

Man With a Geiger Counter. By Josef Muench. 1940-1970.

In 1949, individual Navajos were allowed to acquire ground on mining permits. In the vicinity of the Monument No. 2 lease, Cato Sells, Jessie Black, Harvey Blackwater, Chee Nez, John Yazzie and Thomas CIani obtained mining permits surrounding VCA’s two plots. The permits were assigned to mining companies who located and mined ore on all the permits. VCA let their Monument No. 1 lease expire on December 12, 1952, and the ground was claimed by Cecil Parrish Jr. on Mining Permit (MP) No. 77.

Drilling for Uranium on Oljetoh Mesa. By Josef Muench. 1950-1970.

Monument Valley, (Arizona), photographs compiled by Denny W. Viles, Vanadium Corp. of America. 1948-1966.

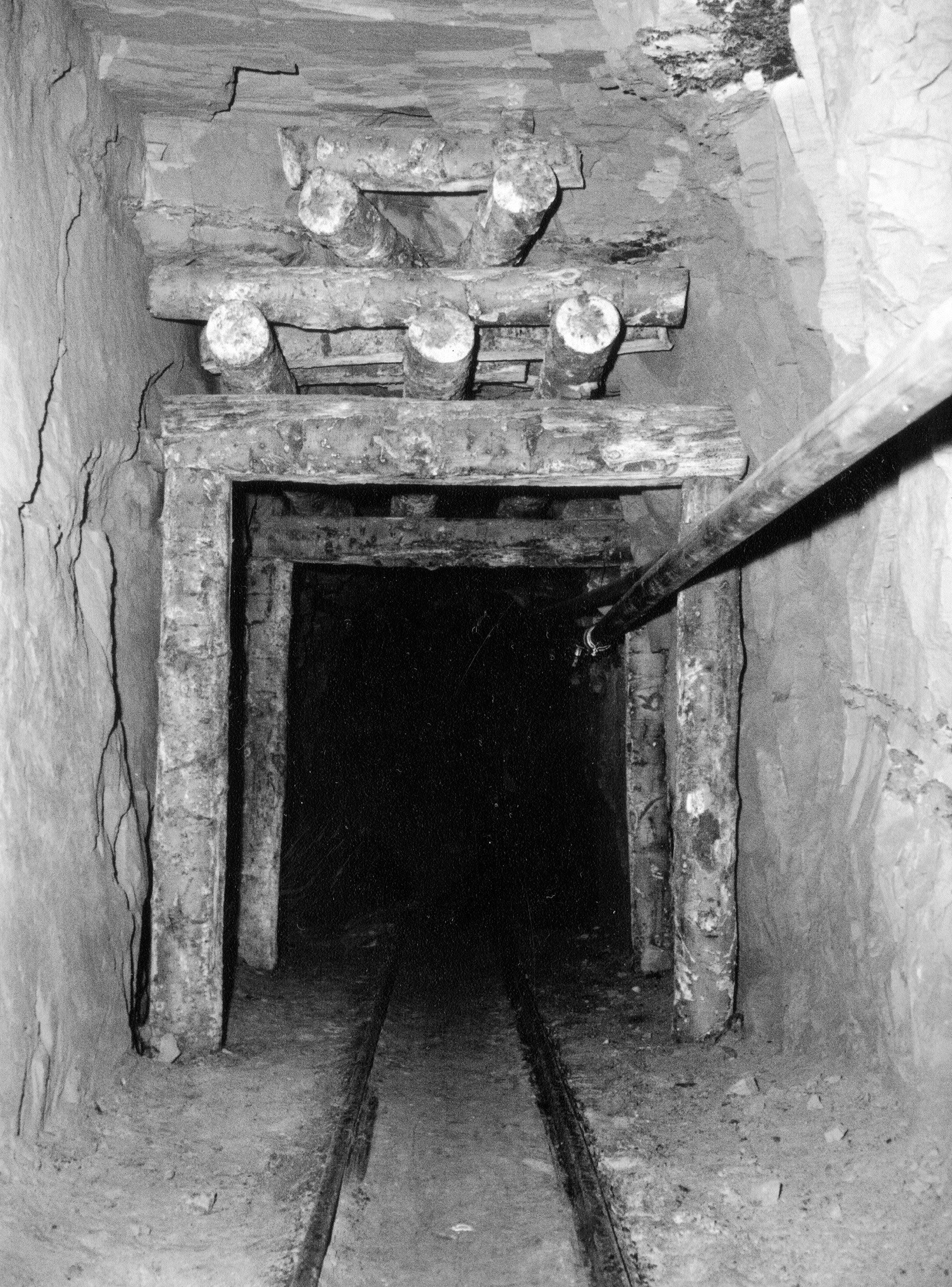

Uranium mining. Timber-framed entrance to mine tunnel. ca. 1955.

Late in 1953, VCA began stripping a large open pit on the Main Ridge where mining had occurred in 11 underground mines. By 1956, the mining area was converted to an open pit 3,500 feet long and 500 feet wide. To upgrade low grade material, VCA operated a mechanical sand-slime upgrader plant at the mine site from mid-1955 until June 1964. This plant separated the uranium-vanadium minerals from the sand grains. Material which averaged 0.04%-0.09% U308 became ore that averaged 0.40%- 0.80% U3O8. On July 20, 1959, VCA modified their original 1943 lease to include the adjacent mining permits of the individual Navajos. The amended lease consisted of three parcels of land totaling 220.69 acres on Yazzie Mesa, Main Ridge and South Ridge.

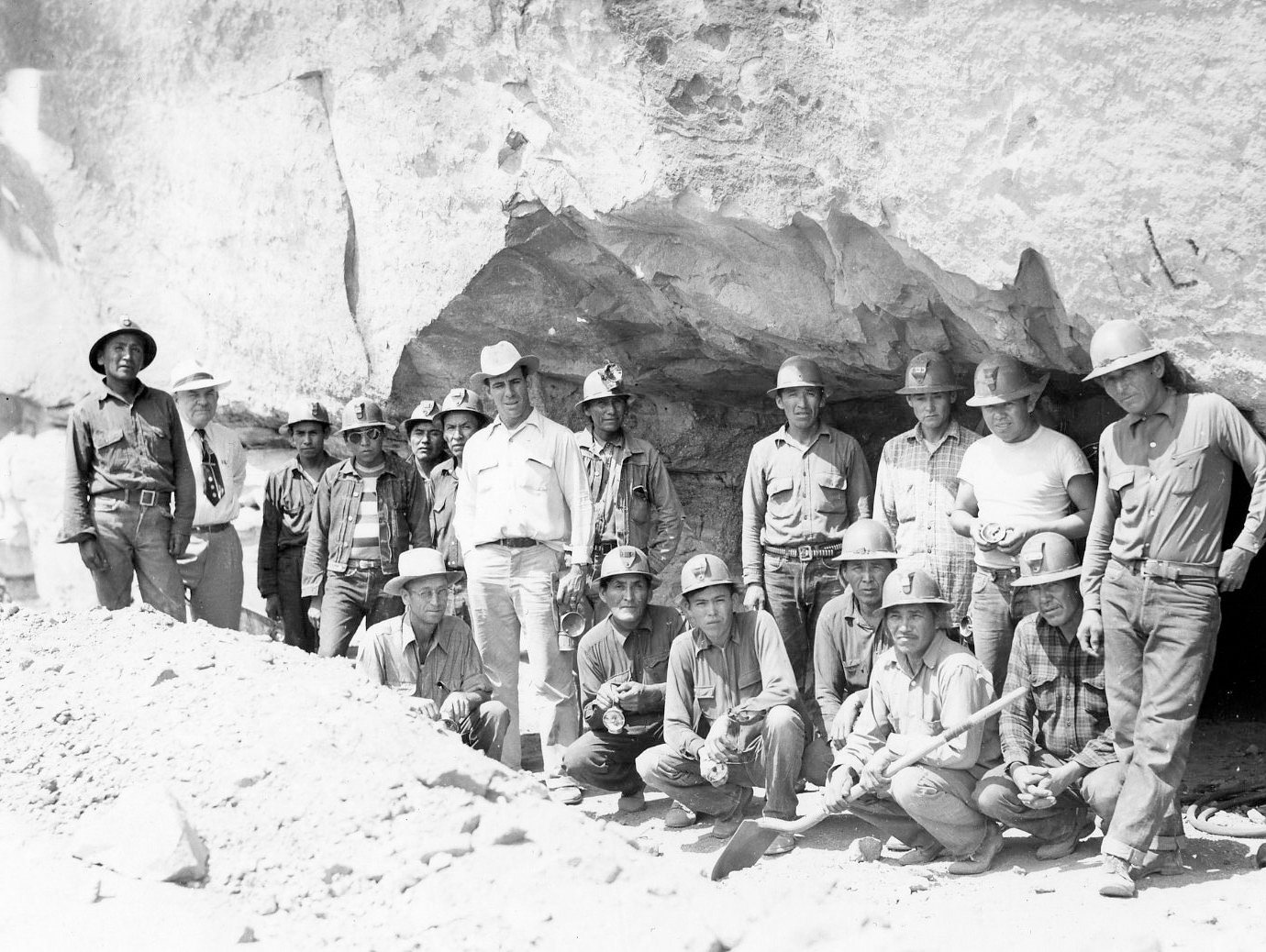

Utco Uranium Corporation. Navajo miners near Cameron, Arizona. 1956.

Dennis Ward Viles with a miner drilling for carnotite ore in the underground tunnel at the Monument #2 Mine north of Kayenta, Arizona. 1950-1959.

In 1953, Seth Bigman acquired MP-73 for 600 acres 3 miles north, northwest of the Monument No. 1 mine. Drilling by the Industrial Uranium Co. in 1954 located the Moonlight ore body on the permit. By 1955, several other Navajos were obtaining MPs in the area of the Oljeto syncline between Highway 163 and Oljeto Wash. They were anticipating future drilling downdip from the Monument No. 1 mine, where an ore body was being mined on the adjacent Mitten No.2 permit. By 1956, some 25 square miles had been covered by MPs. It was in this area that blind drilling discovered the Bootjack, Starlight, Sunlight, Firelight and Big Chief ore bodies. All of these deposits were below the water table and contained unoxidized uranium, vanadium and copper minerals.

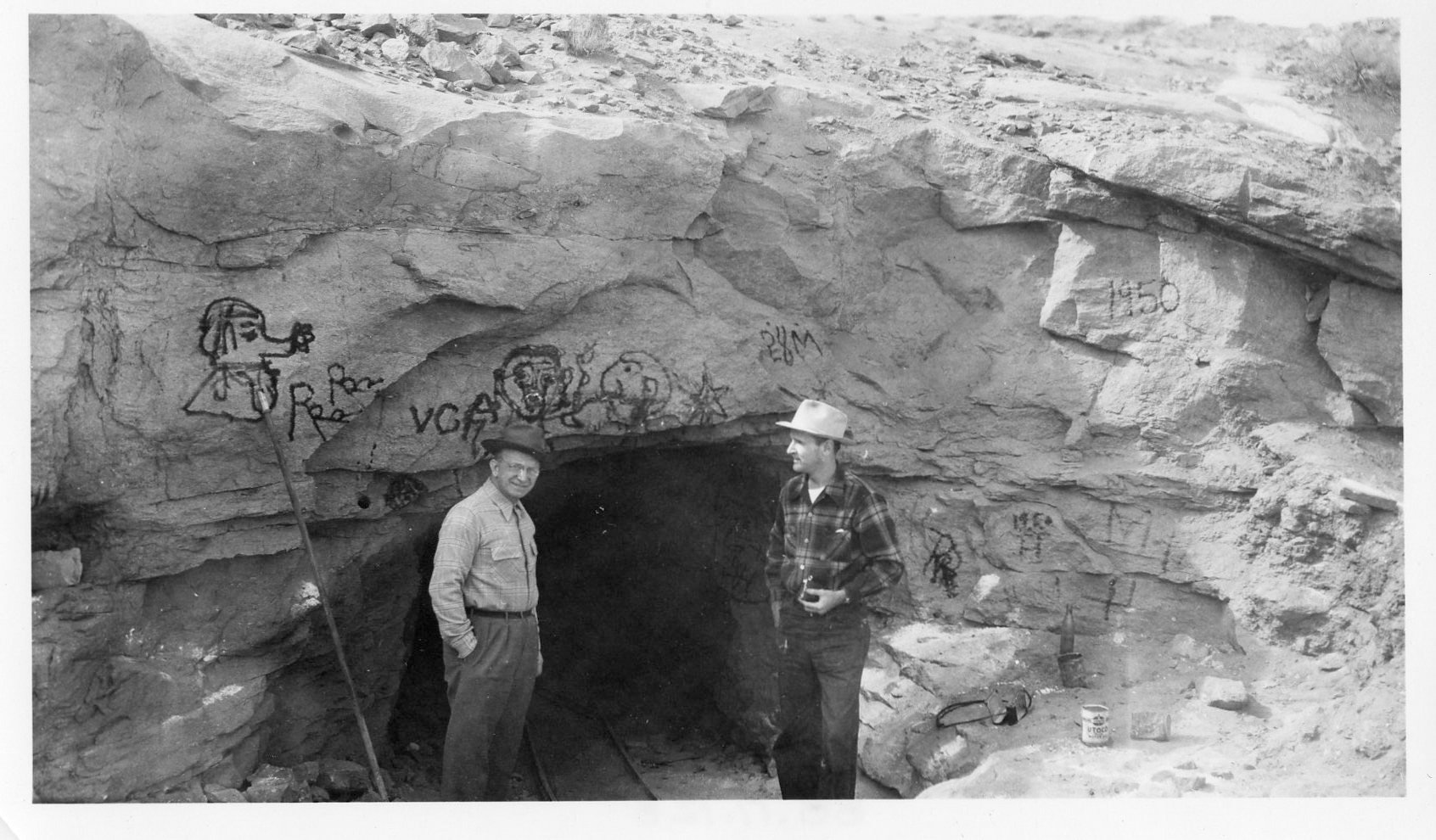

Two men standing outside the tunnel entrance to the Monument #2 Mine. 1950-1959.

Jeep parked behind the sign for the Vanadium Corporation of America's Monument #2 Mine north of Kayenta, Arizona. 1952.

Carnotite mining operation in Monument Valley Arizona. Four Native American miners standing in front of two mine tunnels. The carnotite ore from the mine was processed for uranium and vanadium. 1950-1959.

Due to confusion and conflict regarding MPs in the western portion of Monument Valley, the Navajo Tribal Council withdrew a large area from prospecting and mining on July 19, 1955. The area extended from the San Juan River on the north to Tyende Mesa on the south and from Oljeto Wash west to Nokai Wash. Twenty-nine tracts in the area were offered for mining leases at a sealed bid sale in late 1955. The highest bidder on each tract was given 18 months, beginning on January 24, 1956, to explore its tracts. After exploration drilling, Phillips Petroleum Co. obtained leases on Tracts 10 and lIon Hoskinnini Mesa and Tract 17 on Nokai Mesa. Mines were developed on Tracts 11 and 17.

Ore from Vanadium Corp of America's Monument #2 mine. This is one of the largest producers in the U.S.A. Monument #2 1955.

Photograph of the Monument #2 Mine showing the miners (mostly Native Americans) posing at the mine entrance. 1950-1959.

Production reached an all-time annual high in 1954 when 896,860 pounds of uranium oxide was produced from ores from 8 mines. Eighty-eight percent of this uranium came from mines on VCA’s Monument No. 2 lease. After a small decline, the second highest year was 1959 when 774,670 pounds of uranium oxide were produced from 9 mines. Seventy-three percent of the uranium came from the Moonlight, Bootjack, Sunlight, and Big Chief mines in the Oljeto syncline. After that year, production began to decline. The last shipment from Monument Valley was in 1969, a clean-up of the Monument No. 2 site.

Text by William L. Chenoweth (Consulting Geologist), May 2014, Arizona Geological Survey. From CONTRIBUTED REPORT CR-14-C. Summary of the uranium-vanadium ore production 1947-1969 Monument Valley district, Apache and Navajo Counties, Arizona

Utco Uranium Corporation. Loading uranium ores onto dump trucks near Cameron, Arizona. 1956.

Utco Uranium Corporation. Near Cameron, Arizona. 1956.

Index map of Monument Valley showing the location of the early carnotite leases. By William L. Chenoweth, Consulting Geologist. Prepared For The Arizona Department of Mines And Mineral Resources, October 1984, Grand Junction, Colorado.

Historical photographs from Colorado Plateau Archives (Northern Arizona University, Cline Library) and Mines Repository (Colorado School of Mines, Arthur Lakes Library).

Radioactive Waste

Mexican Hat Disposal Site

The Mexican Hat disposal site is located on the Navajo Reservation in southeast Utah, 1.5 miles southwest of the town of Mexican Hat and 1 mile south of the San Juan River. The site is 10 miles north of the Utah-Arizona border and approximately 15 miles north of the Monument Valley processing site. The site is also the location of a former uranium ore processing mill. Texas-Zinc Minerals Corporation constructed the Mexican Hat mill on land leased from the Navajo Nation and operated the facility from 1957 to 1963. Atlas Corporation purchased the mill in 1963 and operated it until it closed in 1965. A sulfuric acid manufacturing plant operated at the site from 1957 to 1970. Control of the site reverted to the Navajo Nation after the lease expired in 1970.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) completed surface remedial action at the site in 1995. Radioactive materials from the former upper tailings pile, demolished mill structures, and 11 vicinity properties were relocated and placed in a disposal cell constructed at the location of the former lower tailings pile. An additional 983,000 cubic yards (1.3 million dry tons) of tailings and associated waste were hauled from the Monument Valley, Arizona, Processing Site approximately 15 miles to the south and placed in the cell on top of contaminated materials from the Mexican Hat site. A total of approximately 3.6 million cubic yards (4.4 million dry tons) of residual radioactive materials were stabilized in the Mexican Hat disposal cell.

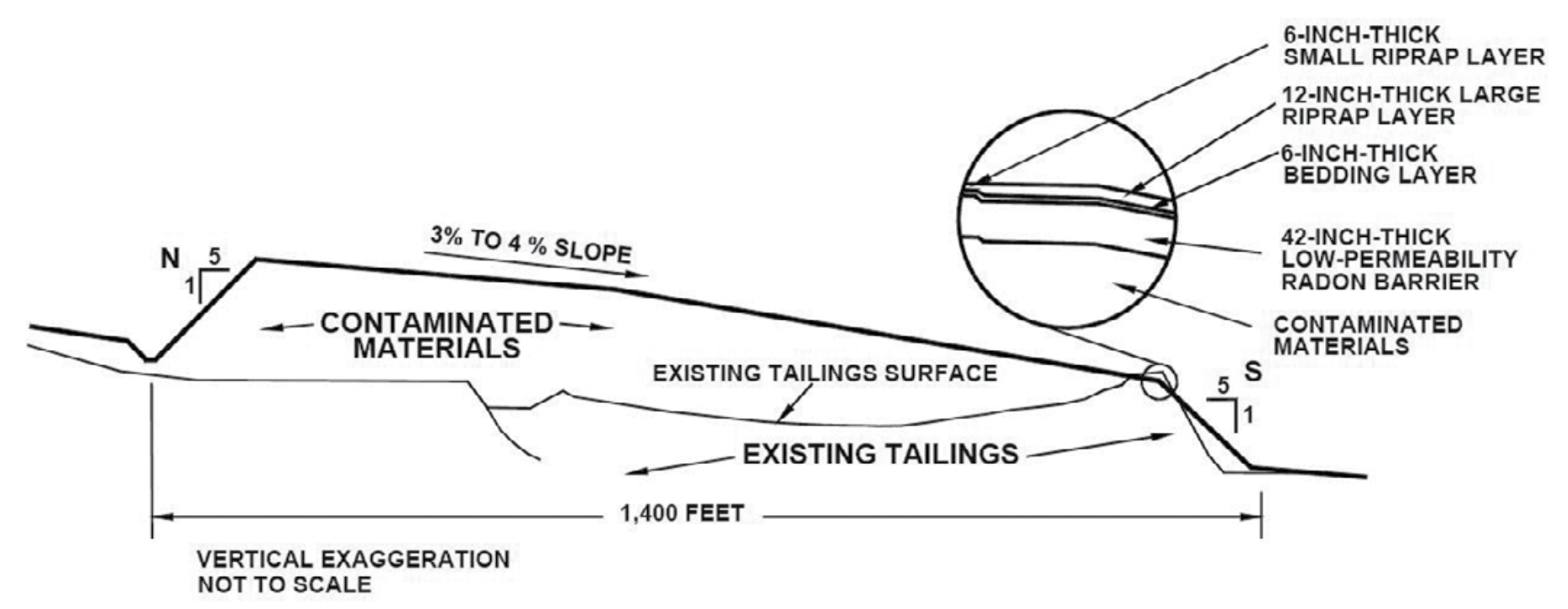

The cell occupies an area of 68 acres on the 119-acre site. It abuts a rock outcrop on its south end and rises approximately 50 feet above the surrounding terrain to the north, east, and west. A posted barbed wire perimeter fence surrounds the cell. Residual radioactive materials in the cell were compacted before being covered. The cover of the disposal cell is a multicomponent system designed to encapsulate and protect the contaminated materials.

The cover is composed of (1) a low-permeability radon barrier (first layer placed over compacted tailings), (2) a bedding layer of sand and gravel placed as a capillary break, and (3) a rock (riprap) erosion protection layer. The cell design promotes rapid runoff of precipitation to minimize leachate. The cell cover was constructed with a 2 percent grade sloping to the north and east. Runoff water flows down the 20 percent side slopes into the surrounding rock apron and exits the cell via three engineered toe drains that drain into existing arroyos north and east of the cell.

The site location and design were selected to minimize the potential for erosion from on-site runoff or storm water flow. All surrounding remediated areas were regraded and reseeded with native plants. Existing gullies in the vicinity of the cell were armored with riprap that was keyed into competent rock to minimize erosion. Riprap-protected diversion ditches were installed to direct surface runoff water away from the cell.

The disposal cell is designed to be effective for 1,000 years, to the extent reasonably achievable, and, in any case, for at least 200 years.

Text from the Mexican Hat, Utah, Disposal Site Fact Sheet by the Department of Energy, Legacy Management.

Typical North-South Cross Section of the Mexican Hat Disposal Cell.

Tuba City Disposal Site

The Tuba City, Arizona, Disposal Site is within the Navajo Nation and close to the Hopi Reservation, approximately 5 miles east of Tuba City and 85 miles northeast of Flagstaff, Arizona. The Rare Metals Corporation and its successor, El Paso Natural Gas Company, operated a uranium mill at the site between 1956 and 1966. During its 10 years of operations, the Tuba City mill processed about 800,000 tons of uranium ore. The milling operations created low-level radioactive mill tailings, a predominantly sandy material. The tailings were conveyed in a slurry from the mill to evaporation ponds at

the site. These ponds covered an area of 33.5 acres, and windblown tailings affected an additional 250 acres northeast of the mill site. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) began surface remedial action at the Tuba City site in 1988. All uranium mill tailings from the on-site piles, debris from demolished mill buildings, and windblown tailings were moved and stabilized in an engineered disposal cell on-site. DOE completed site cleanup in 1990.

The disposal site is approximately 6,000 feet northwest of and 300 to 400 feet in elevation above Moenkopi Wash, an intermittent stream that drains to the southwest into the Little Colorado River. The disposal site lies at an elevation of approximately 5,100 feet above sea level on the middle of three alluvial terraces associated with ancestral flows in Moenkopi Wash. Thin surficial deposits of unconsolidated dune sand and alluvial gravels overlie the Navajo aquifer, which is the main aquifer near the Tuba City site and is regionally vast within sedimentary deposits comprising the Navajo Sandstone Formation. The saturated thickness of the aquifer near the disposal cell is about 500 feet, although within 2,000 feet south of the disposal cell the aquifer thins rapidly because of topography and regional groundwater discharge at Moenkopi Wash. Depth to groundwater ranges from about 60 to 75 feet below land surface.

North-South Cross Section of the Tuba City Disposal Cell.

Historical milling operations contaminated groundwater in the Navajo aquifer. Contaminants infiltrated from the mill’s tailings impoundment to the uppermost part of the aquifer and have been detected 2,500 feet south of the historic mill location. Groundwater contaminants with concentrations that exceed their standards in 40 CFR 192 are molybdenum, nitrate, selenium, and uranium. High levels of sulfate are also present in the groundwater. Although sulfate is not regulated in

40 CFR 192, it is a mill-related contaminant and is present at concentrations exceeding natural background. A cleanup goal for sulfate was determined in consultation with Navajo and Hopi agencies.

Text from the Tuba City, Arizona, Disposal Site Fact Sheet by the Department of Energy, Legacy Management.

Monument Valley Processing Site

Uranium ore-processing mill operated between 1955 and 1968.

The Monument Valley processing site is located on the Navajo Nation in northeastern Arizona, approximately 15 miles south of Mexican Hat, Utah, on the west side of Cane Valley. A uranium ore processing mill operated at the site from 1955 to 1968 on property leased from the Navajo Nation. The mill closed in 1968, and control of the site reverted to the Navajo Nation. Most of the mill buildings were removed shortly thereafter.

Contaminated mill waste was removed between 1992 and 1994. Contaminated material from the Monument Valley Processing Site was transported to the Mexican Hat Disposal Site, approximately 15 miles north of the site.

Uranium was first discovered in 1942 approximately 0.5 mile west of the site. From 1955 until 1964, ore at the site was processed by mechanical milling using an upgrader, which crushed the ore and separated it by grain size. The finer- grained material, which was higher in uranium content, was shipped to other mills for chemical processing. Coarser- grained material was stored on-site and later reprocessed at the site through a sulfuric acid batch leach process that was used at the mill from 1964 until 1968. The milling process also produced radioactive mill tailings, a predominantly sandy material.

Monitored well. 2022.

Source materials and other site-related contamination were removed during surface remediation at the site from 1992 through 1994. All contaminated materials from the Monument Valley processing site were transported north (approximately 15 miles) and stabilized in the Mexican Hat disposal cell. However, analyses of subpile soil samples (samples collected beneath the “footprint” of the former tailings piles) at the site indicate contaminants in these soils may be a continuing source of groundwater contamination. Ammonium in the subpile soil can degrade to contribute to nitrate contamination in groundwater.

Monument Valley Processing Site today (2022).

Groundwater at the former processing site is present in three geological units: the unconsolidated alluvial sand (uppermost aquifer), the underlying Shinarump Member of the Chinle Formation, and the De Chelly Sandstone Member of the Cutler Formation, the deepest of the three aquifers. Only the alluvial and De Chelly aquifers show evidence of milling-related contamination. Although a distinct plume is not present, contamination in the De Chelly aquifer is limited to a small, isolated area where uranium concentrations in samples collected from a few monitoring wells have intermittently exceeded the groundwater standard in 40 CFR 192; however, an exceedance has not been observed since 2015. Historically, the De Chelly aquifer was used to supply production water for the milling operation. Supporting information indicates that pumping from this source can draw down uranium contamination from the overlying alluvium into the De Chelly aquifer. Uranium in the alluvial aquifer is also generally limited to this same isolated area where the former production wells are located.

Approximately 600 million gallons of water are contaminated in the alluvial aquifer. Nitrate, sulfate, and uranium are the contaminants of concern in groundwater at the site. Nitrate and sulfate contamination in alluvial groundwater has migrated more than 6,000 feet north of the former mill site.

Contaminated well in Cane Valley near Navajo settlement.

Institutional controls at the site include fencing around the phytoremediation areas to prevent grazing by livestock and wildlife and to maximize plant growth. DOE is working with the Navajo Nation to restrict access to contaminated groundwater during the remediation period. A domestic water supply system was completed in 2003 to provide potable water to all Cane Valley residents. The project was jointly funded through an interagency agreement between the Indian Health Service and DOE. The project also consisted of the installation of individual septic systems and electricity distribution to approximately 33 households in Cane Valley. The Navajo Tribal Utility Authority retains responsibility for operation, monitoring, and maintenance of the water supply system.

Alluvial Groundwater Contaminant Plumes and Pilot Study Areas at the Monument Valley, Arizona, Processing Site.

Text from the Monument Valley, Arizona, Processing Site Fact Sheet by the Department of Energy, Legacy Management.

Contaminated Land & Water

Sign at A & B No. 2, an abandoned uranium mine near Cameron, Arizona.

From 1944 to 1986, 3.9 million tons of uranium ore were chiseled and blasted from the mountains and plains. The mines provided uranium for the Manhattan Project, the top-secret effort to develop an atomic bomb, and for the weapons stockpile built up during the arms race with the Soviet Union.

Private companies operated the mines, but the U.S. government was the sole customer. The boom lasted through the early ‘60s. As the Cold War threat gradually diminished over the next two decades, more than 1,000 mines and four processing mills on tribal land shut down.

The companies often left behind radioactive waste piles and open tunnels and pits. Few bothered to fence the properties or post warning signs. Federal inspectors seldom intervened.

Over the decades, Navajos inhaled radioactive dust from the waste piles, borne aloft by fierce desert winds.

Upgrader structure on AUM 457 near Cameron, Arizona. The remnants of a concrete structure called an “upgrader”, which was meant to increase the concentration of uranium in the ore from local mines.

They drank contaminated water from abandoned pit mines that filled with rain. They watered their herds there, then butchered the animals and ate the meat.

Their children dug caves in piles of mill tailings and played in the spent mines. Many lived in homes silently pulsing with radiation. Today, there is no talk of cancer immunity in the Navajos.

The cancer death rate on the reservation — historically much lower than that of the general U.S. population — doubled from the early 1970s to the late 1990s, according to Indian Health Service data. The overall U.S. cancer death rate declined slightly over the same period.

Though no definitive link has been established, researchers say exposure to mining byproducts in the soil, air and water almost certainly contributed to the increase in Navajo cancer mortality.

Barricaded entrance of the John M. Yazzie No. 1 uranium mine in Cane Valley, Arizona.

The government has never conducted a comprehensive study of the health effects of uranium mining on the reservation. But individual scientists working on their own have documented sharply elevated cancer rates near old mines and mills. High concentrations of uranium, arsenic and other heavy metals have been found in one out of five drinking-water sources sampled.

Particularly toxic were the “hot” houses built with radioactive debris.

In every corner of the reservation, sandy mill tailings and chunks of ore, squared off nicely by blasting, were left unattended at old mines and mills, free for the taking. They were fashioned into bread ovens, cisterns, foundations, fireplaces, floors and walls.

Navajo families occupied radioactive dwellings for decades, unaware of the risks.

Over the years, federal and tribal officials stumbled across at least 70 such homes, records show. The total number is unknown because authorities made no serious effort to learn the full extent of the problem or to warn all those potentially affected.

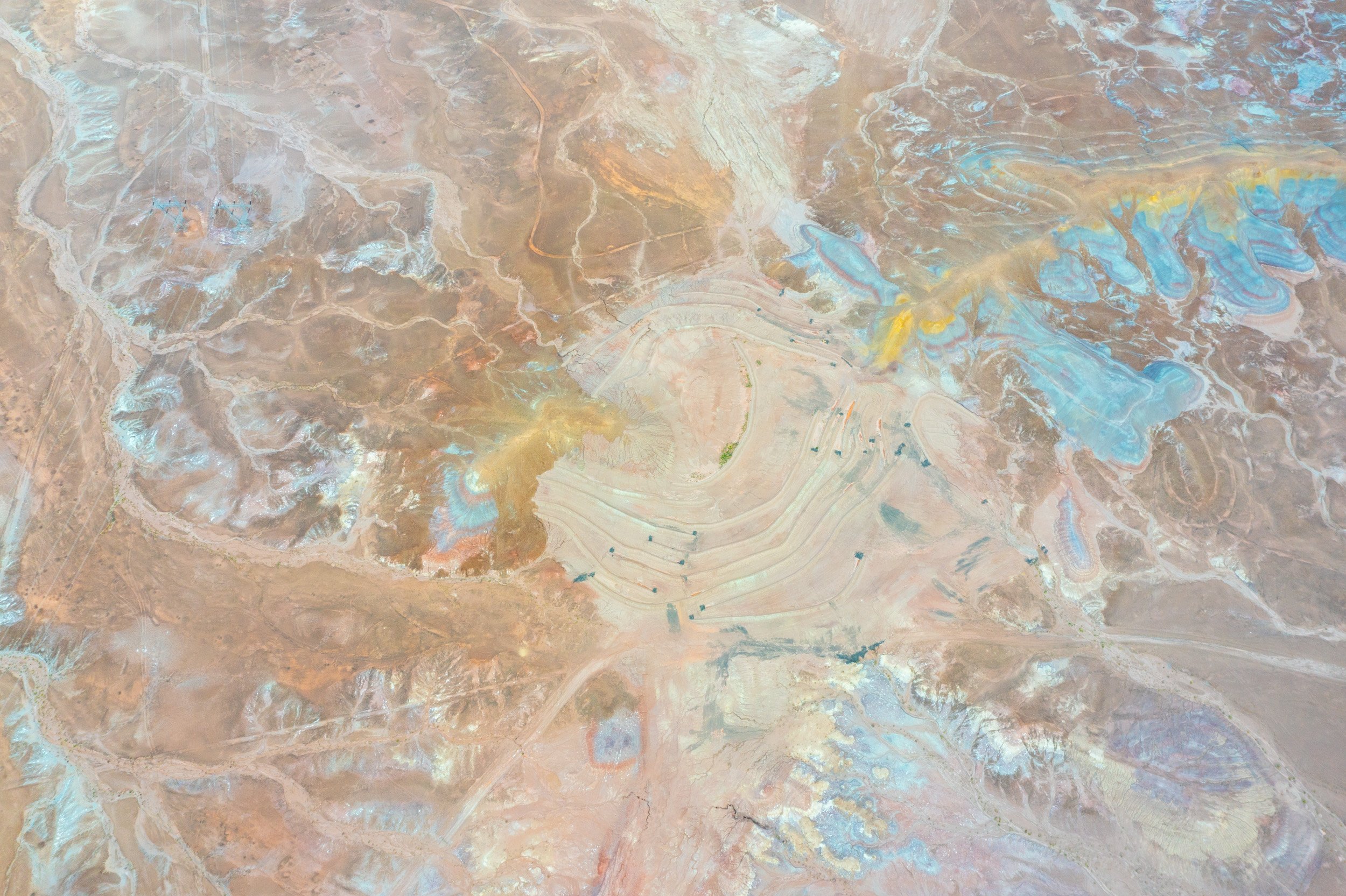

The beauty of the land is deceptive. Aerial photograph of the Charles Huskon No. 1 abandoned uranium mine near Cameron, Arizona.

After years of delay, they fixed or replaced about 20 radioactive houses and then walked away from the problem. Navajos continued to use mine waste as construction material, and the homes were passed down from one generation to the next.

Not until 2000 did one family learn that their hogan was dangerous. By then, they had raised three children and sheltered a host of other kin while the uranium decayed. The resulting alpha, beta and gamma rays were invisible; the radon gas was odorless. But the combination greatly increased the chance of developing fatal lung cancer, according to a radiation expert who sampled air in the hogan.

By the time of the discovery, the woman had lost her husband, to lung cancer and congestive heart failure. He didn’t smoke, but he’d worked in uranium mines by day and slept, unknowing, in the equivalent by night.

Her grandnephew, too, would soon die of lung cancer, at age 42. He had neither smoked nor mined. But he had lived in the hogan for three years as a teenager.

The dwellings in the Holiday family compound faced east toward dawn, in accordance with Navajo tradition. Behind them loomed the mesa, with a pale green uranium stain that started at the old mine and pointed down the cliff.

Radioactive waste from the Monument No. 2 mine was disposed into the wash. Later it was covered with a thick layer of soil, leaving an ugly scar in the unique Monument Valley landscape. Run-off water digs deep ditches, unearths mine waste and washes radioactivity into Cane Valley Wash and into the San Juan River.

Erosion compounds the problem. Desert winds constantly wear away the earthen caps at the mines, exposing chunks of radioactive ore. Gullies eat into buried pit mines, allowing rainwater to course through irradiated soil and contaminate groundwater.

Now, with a renewed push for nuclear power driving up uranium prices, the mining industry wants to extract more from the still-vast Navajo reserve. Tribal leaders are resisting.

By treaty and law, the United States is responsible for the tribe’s welfare, Navajo President Joe Shirley Jr. noted. But the government’s response to the Cold War contamination has been half-hearted, he said.

“It’s an emergency that is not being treated like an emergency,” he said. “Where is our guardian?”

Visible remnants from the John M. Yazzie No. 1 mine cleanup. The open-pit mine and mine waste were covered with clean soil and rocks. Rain water penetrates the top cover, surfacing low-level radioactive uranium ore and yellow carnotite.

Similar problems soon became evident in other parts of the reservation. In 1979, employees of the tribe’s newly created environmental commission escorted a television crew to the hamlet of Oaksprings, Arizona, to interview former miners.

In one house, a tribal staffer offhandedly stuck a Geiger counter against a wall. It screamed.

By April 1980, the tribe had found 16 more Oaksprings houses with uranium. The tribal chairman, Peter MacDonald, called together representatives of Navajo agencies, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service, and “directed that the homes be replaced immediately,” recalled Harold Tso, then the Navajo environmental director. “We were to work together and get a plan.”

Tso cobbled together enough federal money to replace a handful of houses. The tribe evicted the other families in the spring of 1981. They were left to find shelter wherever they could.

There was no money to dismantle the condemned structures. Many still stand, including the log cabin that Clifford Frank built in the early ‘60s for his family of eight. He mixed cement for the foundation with rocks from the uranium mine where he worked. Then he invited a Christian Reformed minister to bless the house.

When the tribe padlocked the cabin years later, Frank was furious. But there was little he could do. Frank, a nonsmoker in his 50s, was in the Indian Health Service hospital in Shiprock, New Mexico, slowly succumbing to lung cancer.

Contaminated well used to water a corn field and water melons. The groundwater can not be used as drinking water. However, since hauling clean drinking water for agriculture and livestock is costly and time-consuming, local residents have no choice but to use existing and unsafe water.

Carnotite, a radioactive, yellow mineral and ore of uranium, found on the surface of a cleaned up mine in Cane Valley, Arizona. In the Navajo language uranium is called "leetso", which means yellow dirt.

Unmonitored spring in Cane Valley that provides water year-round used for livestock. In hot summer months horses and wild donkeys stay close to a reliable water source.

Abandoned well in Cane Valley Wash near the abandoned Harvey Blackwater No. 4 uranium mine. Groundwater in Cane Valley is contaminated with unhealthy levels of uranium, nitrate, and arsenic caused by chemical processing of uranium ore.

Text: Excerpt from “A peril that dwelt among the Navajos” by Judy Pasternak.

Published in the Los Angeles Times on November 19, 2016.

Sacred Places

"Protect The Sacred". Sign in Kayenta, Arizona. Also, the name of a nonprofit organization that educates and empowers the next generation of Native leaders to strengthen Indigenous sovereignty.

Text by Brad Olsen, 2008, from Sacred Places North America: 108 Destinations.

The Navajos In the 15th century, the Dine (the original Navajo name meaning “The People”) migrated south from the far northern tundra regions of North America into the Central Plains. A hundred years later part of the tribe migrated once again, this time to what is today northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico. Here they encountered the Pueblo Indians already established on the land for many centuries. Similar to the Romans adapting to the traditions of older Greek mythology, the Navajo emulated the legends of their older Hopi counterparts. Navajo legend describes the Dine as having to pass through three different worlds before arriving on this earthly plane, called the fourth world, or the Glittering World. On this plane the Dine believe there are two classes of beings: the Earth People, and the Holy People.

The Earth People are the Navajo themselves, while the Holy People are the equivalent of Navajo gods. The Holy People are said to have the power to aid or harm Earth People, and centuries ago the Holy People taught the Dine how to live correctly in their everyday life. They were taught how to harmoniously exist with Mother Earth, Father Sky, animals, plants, and insects. The Holy People assisted the First Man and the First Woman out of the third world into the Glittering World, where the first man and woman found pueblos already existing. The Holy People put four sacred mountains in four different directions: Mount Blanca near Alamosa, Colorado to the east; Mount Taylor near Grants, New Mexico to the south; the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, Arizona to the west; and Mount Hesperus near Durango, Colorado to the north. Collectively these mountains established the ancestral Navajo land of the fourth world.

Petroglyphs (rock carvings) by Native Americans (Anasazi, Navajo, and Pueblo) at a sacred site near Tuba City, AZ tell the story of ancient indigenous tribes and how they hunted deer, grew corn and lived in harmony with Mother Earth.

The Dine (named the “Navajo” by Spanish explorers in 1540) mark their emergence into the fourth world from a hole in the La Plata Mountains of southwestern Colorado. The story of Dine creation is recounted in the tribe’s most important ceremony, called the Blessing Way Rite. This ritual had been given to the tribe shortly after the emergence of the Holy People who created the natural world and humans. Navajo religious doctrine holds that the first Blessing Way ceremony was performed during the emergence of First Man and First Woman. The Navajo people and the Blessing Way came into being simultaneously and symbiotically, thus establishing the ceremony’s importance for all time. The two-day ceremony begins by recounting in song First Man’s creation of humankind. The next day more songs are sung about other stages of the world’s creation, and a bathing ritual in yucca (cactus) suds is performed to symbolize renewal. Crushed flower blossoms, corn meal, and pollen are sprinkled upon the ground to bless and bring good fortune to the Navajo people. The ceremony concludes with a 12-stanza song designed to satisfy the Holy People and reinforce the Navajo ideal of harmony between humans and nature. Blessing Way is performed at least once every six months for each Navajo family, in addition to special occasions such as weddings, impending births and the consecration of a new home. The Navajo regard this ceremony as fundamentally life-giving because the Dine founders bestowed it, defining the tribe and its world purpose. Indeed, the Navajo believe that when the Blessing Way ceremony ceases to be performed, the world will come to an end.

Anasazi cliff dwellings from the 12th century. A sacred place no one is allowed to enter.

Painted pottery was used for ceremonies. Shards show where Navajo used to set winter camp and shelter from cold winds. Navajo belief that pottery shards are sacred and should never be touched.

Totem Pole (right) and Yei Bi Chei (left), rock spires and holy, god-like figures for the Navajo in Monument Valley. The rock formation is seen as spiritual dancers emerging from a Hogan. Yei Bi Chei (Yébîchai ceremony) is a Night Chant and known as healing dance at a sacred nine-night ceremony in which masked dancers personify the gods.

Monument Valley In a high desert climate where fresh water and wild game are scarce, the prehistoric Anasazi Indians thrived in the area for over 700 years. The Anasazi first came to Monument Valley at least 1,500 years ago, constructing cliff dwellings and carving mysterious petroglyphs before suddenly disappearing. Some Navajos claim there are a few Anasazi ruins in Monument Valley that no white man has ever seen. The Athapaskan speaking Navajo arrived hundreds of years after the Anasazi disappeared, adapting well to the arid environment. In Monument Valley, where the past seems eternal and history is all around, the Navajo have maintained harmony with “Mother Earth and Father Sky,” blending what is modern with what is traditional in this fourth, or Glittering World. The valley features spires, buttes, and mesas towering over the mile-high terrain by a thousand feet (300+ m) or more. The landscape speaks eloquently of nature’s own creation technique by using wind, erosion, rain and time. Much of Navajo culture remains unchanged and preserved in Monument Valley. Their art has been passed down from generation to generation and many artistic techniques continue as they have since ancient times. Potters still use the coil method, adding liquid colored clay to create exquisite designs. Hand woven carpets and other textiles continue to be dyed and spun at Monument Valley. Traditional homes called hogans dot the landscape. The domed, hexagon-shaped hogan is regarded as a sanctuary to the families who take up permanent residence.

Sand Spring situated in the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park.

Native Americans usually assigned religious significance to their dwellings, which would oftentimes double as ceremonial centers. For example, the hogan entrance always faces east toward the rising sun. Some of the 300 Navajos still living in Monument Valley reside in the traditional earthen homes, although most now include modern stoves for heat and cooking. Monument Valley is among the most photographed landscape in the world. The Navajo Nation considers it a healing place with deep spiritual meaning. Several important Navajo ceremonies started within Monument Valley, including the origination of the Squaw Dance and the Yei Bi Chei Dance. Both dances were first held in Monument Valley and continue to be performed at different locations on the reservation where needed. Yei Bi Chei was a holy figure to the Navajo. Distinguished Navajo men dress as the Yei Bi Chei and dance for healing purposes in a very sacred nine-day ritual called the Night Way Ceremony. A prominent rock formation in Monument Valley resembles a line formation of several different Yei dancers. The Squaw Dance involves winter stories about animals when they are hibernating. In addition to group ceremonies, individual Navajo families have their own favored “prayer places” in different locations around Monument Valley.

More than 60 uranium mines were operated between 1944 and 1962 near Monument Valley, a sacred site of the Navajo Nation. Monument Valley, with its world famous sandstone buttes, was a popular backdrop for Western movies. The Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park is a touristic area that attracts 350,000 visitors each year. Very little information about uranium mining and the health issues caused by it is displayed at the visitor center.