Bärgwätter / Swiss Mountain Weather

A meditation on water, weather, and the changing Alps

After eight years documenting water scarcity in the arid American Southwest, I returned to my homeland—the Swiss Alps—where water has never been scarce. Or so I thought.

The Weather I Didn't Know I Was Waiting For

In July 2025, I spent two and a half weeks traversing the Bernese Oberland, sleeping in mountain huts and hiking through landscapes I've known since childhood. The forecast promised disappointing weather: clouds, fog, rain. Half the hikers at Blüemlisalphütte canceled their reservations. But I've learned something living in San Diego's relentless sunshine—moody weather reveals more than perfect blue skies ever could.

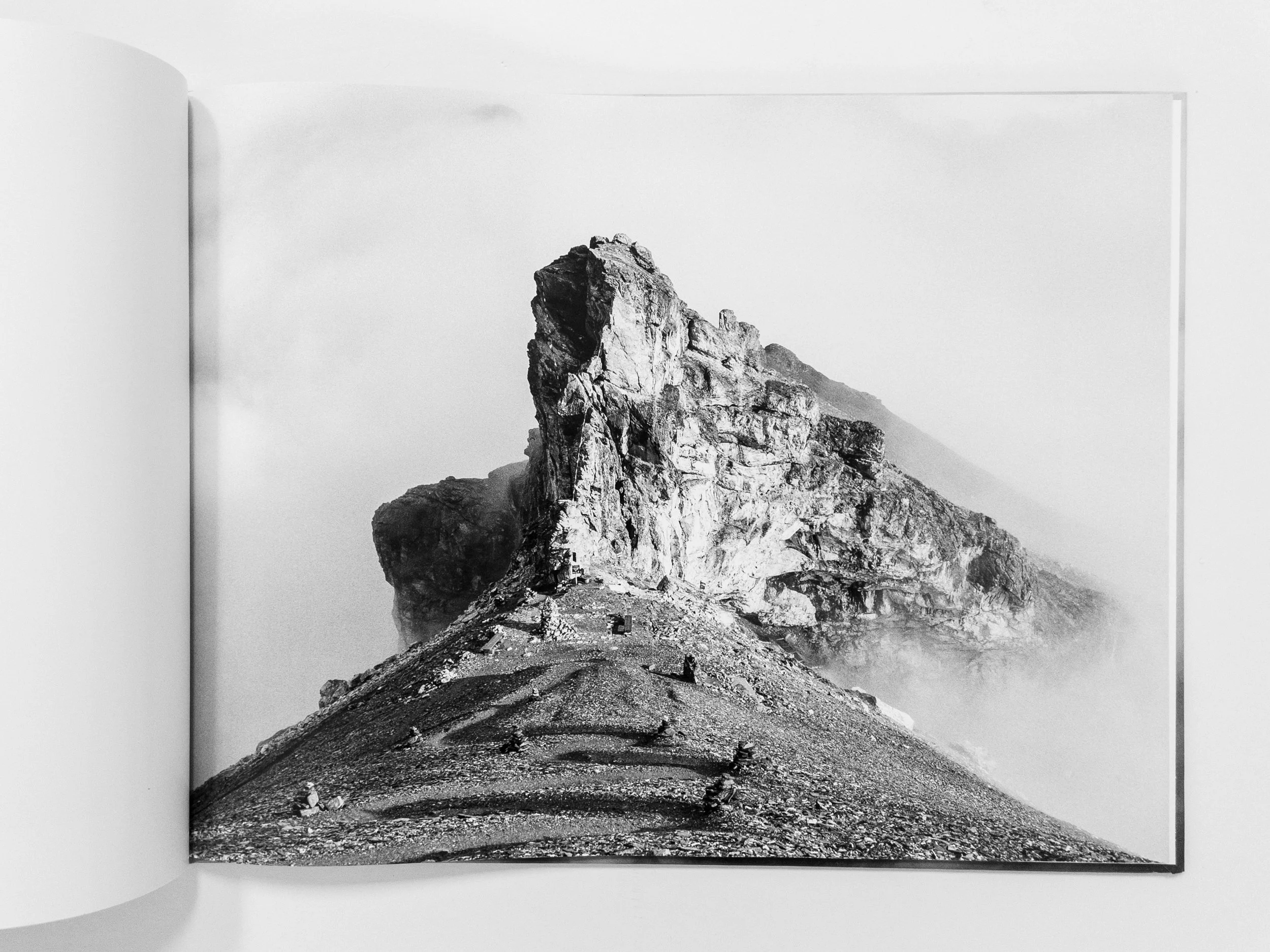

Through my medium format camera, loaded with black and white 120 film, I captured what the Swiss call bärgwätter—that particular mountain weather when clouds part momentarily, when peaks emerge from fog, when light breaks through in ways that feel like revelation. Every day brought these fleeting windows of clarity, mountain summits appearing and disappearing like memories.

Following Water from Source to Scarcity

The contrast couldn't be starker. In the Colorado River Basin, where I've spent years documenting Lake Powell at 30% capacity and Native tribes unable to access their water rights, every drop is contested, measured, fought over. Here in Switzerland, water cascades everywhere—the thundering Engstligen Falls, countless unnamed streams, the rushing torrents in the Choleren gorge where I walked suspended above the fury.

But something has changed since my childhood. The glaciers are retreating.

From the Blüemlisalp lodge, I watched the Blüemlisalpgletscher—a glacier that once flowed robust and eternal—now pulling back into its valley, exposing raw rock that hasn't seen sunlight in millennia. At Oberhornsee, a tiny alpine lake below another glacier, we found remnant snowfields from last winter, but they felt precarious, temporary. The valleys these glaciers carved are becoming monuments to what was.

Generations and Granite

Some connections persist. The Stossboden cabin in the Simmental has sheltered my family for generations. My grandfather maintained it—chopping firewood, making repairs—so his children and their children could know these mountains. I've spent summers and winters here, and now I return with my camera to document not just beauty, but change.

The Swiss Alpine Club huts—Blüemlisalphütte, Fromatthütte—serve as way stations between past and future. These lodges have hosted climbers and hikers for over a century, witness to the Alps' transformation. At Obersteinberg, deep in the Lauterbrunnental, the privately owned hotel offers views of glaciers and waterfalls that grow smaller each season.

What the Clouds Revealed

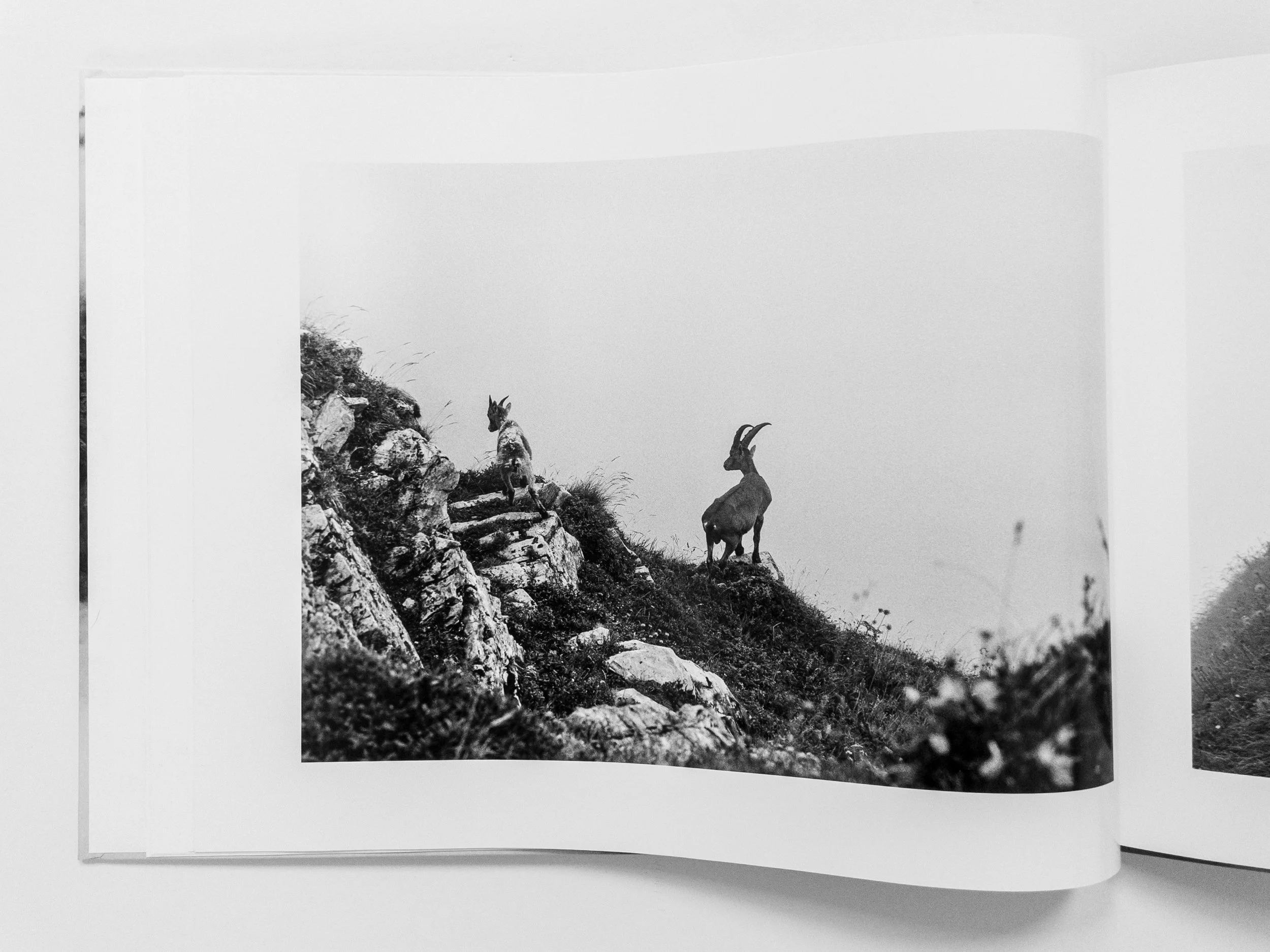

My hikes took me through landscapes both familiar and strange. On Hardergrat, more than twenty ibex grazed near the trail—wild, magnificent, seemingly indifferent to the changing climate around them. I descended through Graagetor, a natural rock arch, feeling the permanence of stone and the impermanence of ice.

The Schynige Platte viewpoint, reached by steep cogwheel train, offered panoramas of peaks—Eiger, Mönch, Jungfrau—emerging from cloud cover. These are the mountains of my childhood, but their white crowns are diminishing. Switzerland's glaciers have lost more than half their volume since 1931, with acceleration in recent decades.

Two Water Stories, One Crisis

Creating bärgwätter—this collection of moody, atmospheric images—forced me to reckon with an uncomfortable truth: the water abundance I grew up with is not permanent. While the American Southwest battles over an over-allocated river, Switzerland faces its own crisis. The glaciers that have reliably fed rivers for millennia are disappearing. The "water towers of Europe" are running dry.

My black and white photographs strip away the distraction of color to reveal essential forms: peaks emerging from cloud, rock exposed where ice once was, water in all its forms—fog, rain, snowmelt, glacial runoff. The monochromatic palette asks viewers to look deeper, to see not just beauty but evidence of change.

Mountains Don't Forget

Walking these trails—from Tschentenalp to Schwandfeldspitz, alongside the Engstligen waterfalls, through the cold darkness of Cholorenschlucht gorge—I carried two cameras: one capturing images, one recording memory. The mountains of my childhood are transforming, just as Glen Canyon is re-emerging from beneath Lake Powell's receding waters.

Both landscapes tell the same story about climate, consequence, and what we're losing. Whether through drought or melt, water is rewriting geography. My work documenting the Colorado River crisis and now these changing Alps becomes a single narrative about our relationship with water—how we use it, waste it, take it for granted until it's gone or irrevocably altered.

The Book and What It Holds

Bärgwätter exists now as an A3 landscape book, large enough to feel the weight of these mountains, the texture of this weather. It's a record of moody days that revealed more than sunshine ever could—a document of a changing homeland, additionally printed in the darkroom with the same care I bring to images of Lake Powell's bathtub rings.

These Swiss mountain photographs join my ongoing "Water Stories" project—a broader investigation into water abundance, scarcity, and justice across two continents. They remind me that environmental crisis takes many forms, and that the abundance I took for granted growing up is as fragile as the desert rivers I now document.

The weather I experienced in July 2025—clouds, fog, rain, those miraculous moments of clarity—wasn't beautiful despite the conditions. It was beautiful because of them. Bärgwätter taught me to see what's really there: a mountain community adapting, glaciers retreating, water flowing toward an uncertain future.